References to Objects#

In this section we will continue to refer to the Point

class created in

the introductory section.

Show code cell content

from numbers import Number

class Point:

"""An (x,y) coordinate pair"""

def __init__(self, x: Number, y: Number):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def move(self, d: "Point") -> "Point":

"""(x,y).move(dx,dy) = (x+dx, y+dy)"""

x = self.x + d.x

y = self.y + d.y

return Point(x,y)

def move_to(self, new_x, new_y):

"""Change the coordinates of this Point"""

self.x = new_x

self.y = new_y

def __add__(self, other: "Point"):

"""(x,y) + (dx, dy) = (x+dx, y+dy)"""

return Point(self.x + other.x, self.y + other.y)

def __str__(self) -> str:

"""Printed representation.

str(p) is an implicit call to p.__str__()

"""

return f"({self.x}, {self.y})"

def __repr__(self) -> str:

"""Debugging representation. This is what

we see if we type a point name at the console.

"""

return f"Point({self.x}, {self.y})"

Variables refer to objects#

Before reading on, try to predict what the following little program will print.

x = [1, 2, 3]

y = x

y.append(4)

print(x)

print(y)

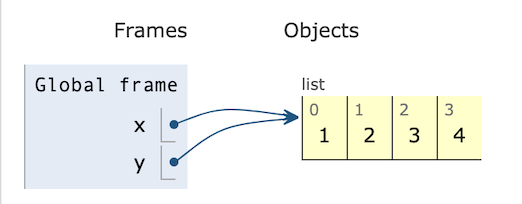

Now execute that program. Did you get the result you expected? If it surprised you, try visualizing it in PythonTutor (http://pythontutor.com/). You should get a diagram that looks like this:

x and y are distinct variables, but they are both references to

the same list. When we change y by appending 4, we are changing the

same object that x refers to. We say that x and y are aliases,

two names for the same object.

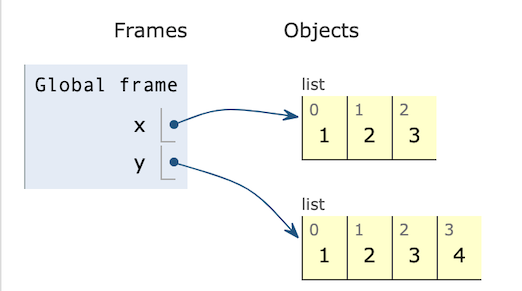

Note this is very different from the following:

x = [1, 2, 3]

y = [1, 2, 3]

y.append(4)

print(x)

print(y)

Each time we create a list like [1, 2, 3], we are creating a distinct

list. In this seocond version of the program, x and y are not

aliases.

It is essential to remember that variables hold references to objects, and there may be more than one reference to the same object. We can observe the same phenomenon with classes we add to Python. Consider this program:

p1 = Point(3,5)

p2 = p1

p1.move_to(7, 9)

print(p2)

(7, 9)

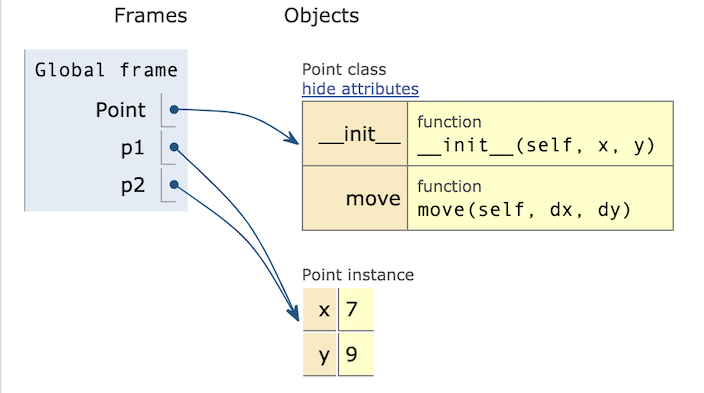

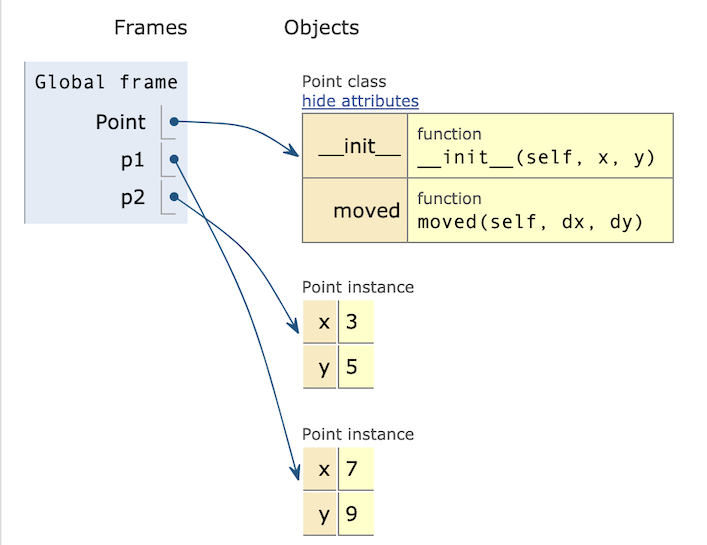

Once again we have created two variables that are aliases, i.e., they refer to the same object. PythonTutor illustrates:

Note that Point is a reference to the class, while p1 and p2 are

references to the Point object we created from the Point class. When

we call p1.move, the move method of class Point makes a change to

the object that is referenced by both p1 and p2. We say that

a method like move mutates an object.

Mutable and Immutable#

There is another way we could have written a method like move.

Instead of mutating the object (changing the values of its fields

x and y), we could have created a new Point object at the

adjusted coordinates:

class Point:

"""An (x,y) coordinate pair"""

def __init__(self, x: int, y: int):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def moved(self, dx: int, dy: int) -> "Point":

return Point(self.x + dx, self.y + dy)

p1 = Point(3,5)

p2 = p1

p1 = p1.moved(4,4)

print(p1.x, p1.y)

print(p2.x, p2.y)

7 9

3 5

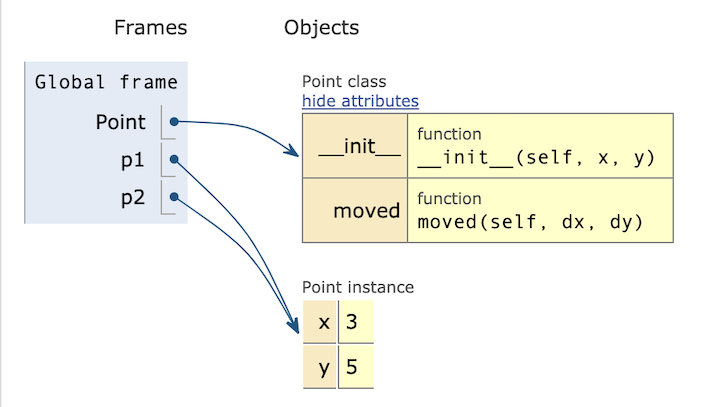

Notice that method moved, unlike method move in the prior example,

return a new Point object that is distinct from the Point object that

was aliased. Initially p1 and p2 may be aliases, after p2 = p1:

But after p1 = p1.moved(4,4), p1 refers to a new, distinct object:

As we saw with the list example, aliasing applies to objects

from the built-in Python classes as well as to objects

from the classes that you will write. It just hasn’t been

apparent until now, because many of the built-in classes

are immutable: They do not have any methods that

change the values stored in an object. For example, when

we write 3 + 5, we are actually calling (3).__add__(5);

The __add__ method does not change the value of 3 (that

would be confusing!) but instead returns a new object 8.

It is typically easier to reason about the behavior of immutable

classes. On the other hand, it may be more efficient to mutate

an object than to return a new object with a small change.

Many of Python’s built-in classes, like str and int, are

immutable to make reasoning easier.

Most of Python’s built-in collection classes, like list and

dict, are mutable for the sake of efficiency.

We will write both immutable classes and mutable classes,

depending on our needs, with a preference for immutable classes

where extra cost is inconsequential.

Aliasing mutable objects is often a mistake, but not always. Later we will intentionally create aliases to access mutable objects. The important thing is to be aware of aliasing and mutation.